Withering-type botanical microscope, 1780

The “Withering-type Microscope” is named for its inventor, Dr. William Withering (1741-1799), an English physician and botanist who graduated with a degree in medicine 1766 in Edinburgh. Inspired by the taxonomical work and systematic classification of Carl Linnæus (1707-1778), Withering (1776) applied the Linnaean taxonomical system of classification to British plants in a seminal, two volume work, A Botanical arrangement of all the vegetables naturally growing in the British Isles. The earliest reference to a small botanical microscope of Withering’s design appeared in the first edition of this book. There, Withering indicated this microscope was developed for field dissections of flowers and other plant parts. While there is no surviving example of this exact design, close relatives of this type do exist, made either completely of brass or of ivory with brass pillars. Ivory models can be tentatively dated to 1776-1785, as by 1787 a newer model with a hollowed stage in an all-brass configuration already predominated. In turn, it was preceded by the brief appearance of a transitional brass model but with solid stage of ivory or horn (seen here). This version is extremely rare and must have been produced in very small numbers. By 1787 all these varieties were not recorded anymore in the literature.

Withering-type botanical microscope, 1780

The “Withering-type Microscope” is named for its inventor, Dr. William Withering (1741-1799), an English physician and botanist who graduated with a degree in medicine 1766 in Edinburgh. Inspired by the taxonomical work and systematic classification of Carl Linnæus (1707-1778), Withering (1776) applied the Linnaean taxonomical system of classification to British plants in a seminal, two volume work, A Botanical arrangement of all the vegetables naturally growing in the British Isles. The earliest reference to a small botanical microscope of Withering’s design appeared in the first edition of this book. There, Withering indicated this microscope was developed for field dissections of flowers and other plant parts. While there is no surviving example of this exact design, close relatives of this type do exist, made either completely of brass or of ivory with brass pillars. Ivory models can be tentatively dated to 1776-1785, as by 1787 a newer model with a hollowed stage in an all-brass configuration already predominated. In turn, it was preceded by the brief appearance of a transitional brass model but with solid stage of ivory or horn (seen here). This version is extremely rare and must have been produced in very small numbers. By 1787 all these varieties were not recorded anymore in the literature.

References: SML: A242712; Goren 2014.

References: SML: A242712; Goren 2014.

Prof. Yuval Goren's Collection of the History of the Microscope

Chapter 2: Natural History in the Seventeenth Century

Johann Franz Griendel von Ach und Wankhausen in Micrographia nova: Battle Between Flea and Louse, 1687

In the 17th century, natural history experienced a significant transformation towards experimental observation. This shift was fueled by new technologies, including the microscope and telescope, as well as the establishment of institutions such as the Royal Society. As a result, older theories, such as spontaneous generation, were increasingly rejected. Notable figures like Jan Swammerdam and Francesco Redi conducted detailed, evidence-based studies on the life cycles and anatomy of insects. Additionally, the field of natural history was influenced by exploration and empire, with naturalists collecting and describing new species from around the world.

Natural history remained largely static throughout the Middle Ages in Europe. Starting in the 13th century, Aristotle's work was rigidly adapted into Christian philosophy, particularly by Thomas Aquinas, which laid the groundwork for natural theology. During the Renaissance, scholars, especially herbalists and humanists, began to return to direct observation of plants and animals in the field of natural history. Many of these scholars started amassing large collections of exotic specimens and unusual creatures. The rapid increase in the number of identified organisms led to multiple attempts to classify and organize species into taxonomic groups, culminating in the system developed by Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus.

The growing interest in natural history captured the attention of the general public. While this interest was primarily focused on objects visible to the naked eye, many fascinating structures became apparent under magnification. For instance, the intricate eyes of insects and the hidden patterns on butterfly wings drew significant interest.

To observe these details, a lens with a basic magnification of around 6X or more was sufficient. Additionally, a method was necessary to stabilize the observed object at the correct focal distance. This could be accomplished simply by impaling the specimen on a pin or needle and adjusting its distance from the lens until it was in focus.

By the mid-17th century, simple and accessible microscopes made from inexpensive materials such as wood, bone, and horn began to appear. These early microscopes not only magnified objects but also included basic systems for stabilizing and focusing specimens at a short distance. While technically any tool that magnifies a close object can be labeled a microscope, a more precise definition includes the existence of a mechanism for fixing and adjusting the focal distance of the observed object.

German Bone Screw-Focusing Microscope, ca. 1650.

This is probably the earliest true microscope in this collection. Various characteristics suggest that it was made in Augsburg, Bavaria, in the mid-17th century. Focusing is achieved by means of a screw with a pin at the end to which the insect or flower under examination is impaled.

The wooden container attached to the microscope was likely added later. An identical microscope is found in the Giordano collection, now part of the Museum of Confluences in Lyon. This microscope is described as Continental, most likely of German origin, but it is not specifically attributed to Augsburg.

Spike-Stand "flea glass" simple microscopes, ca. 1650-1750

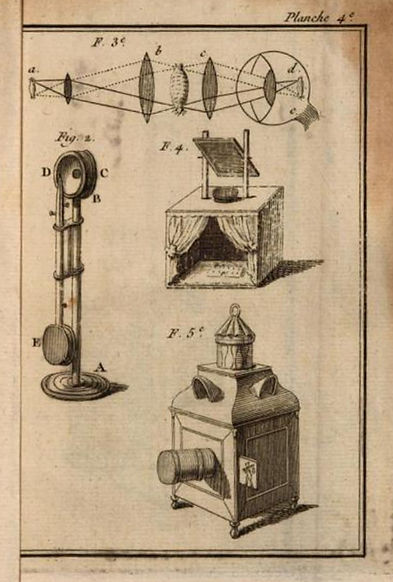

These are early versions of the single microscope, crafted from materials such as bone, horn, or fruitwood. They were used in the Netherlands and German regions from the mid-17th to the mid-18th centuries. Each microscope features a single biconvex lens mounted on a stand, which faces a spike attached to a movable rod or a brass sprung pin. This spike was designed to hold a flower or insect for examination, giving rise to the term "flea glass," an English translation of the Latin name "vitrum pulicarium." Focusing was accomplished by adjusting the spike either backward or toward the lens. A similar microscope can be found in Johannes Zahn's book from 1702.

A similar microscope appears in Johannes Zahn's (1702) book below.

Spike-stand microscope, after Zahn, Johan. 1702. Oculus artificialis teledioptricus sive telescopium. Nuremberg.

Flea, after Johann Franz Griendel. 1687. Micrographia nova sive Nova et curiosa variorum minutorum corporum... Nuremberg.

Bone and Horn Spike-Stand Microscopes, ca. late 17th century to ~1700

These are early Dutch forms of the spike-stand microscope lathe-turned of bone or horn. This early and relatively rare form of the Spike-Stand microscope is more or less similar to Zahn's depiction; the latter was probably turned of wood.

Inv. YG-21-003

© Microscope History all rights reserved

Wood Spike-Stand, ca. 1700-1750

Inv. YG-20-002

This is a more common form of the Spike-Stand microscope, of a type that was probably related with an early stage of the manufacture of optical instruments by the wooden toy craftsmen of Bavaria (mostly Nuremberg), and the "Black Forest" areas of the German lands. This example is an earlier version within this category, which should be dated roughly to the 18th century. Later versions of this class were probably produced as late as the end of the 18th century. The earlier forms of this style of instruments (such as the one seen here), sometimes come with cylindrical cardboard boxes coated with decorated roulette-pattern papers, which unfortunately was not preserved with this specimen. However, absolute dating of these instruments is problematic and the seriation offered here is merely speculative.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

© Microscope History all rights reserved

Early 18th Century Stand Single Microscopes

The single microscope used by Louis Joblot, ca. 1710 (Inv. YG-21-010)

This microscope involves the work of the French researcher Louis Joblot (1645-1723). It seems that among the "Old Regime" of the beginning of microscopy he was wronged by oblivion by the general public, this in the face of the historical memory (very justified in itself) which Antonie van Leeuwenhoek won. A good, concise biography of Joblot is online here and I will not copy it.

In the historical research of the founding generation of intellectual microscopy, Anthony van Leeuwenhoek acquired the frontstage alongside Robert Hooke as a discoverer and observer who laid the foundations for modern microscopy as a science. In fact, it was Leeuwenhoek who made the important breakthrough, as Hooke described mostly objects visible to the naked eye, but under the microscope. Louis Joblot's place is absent from the list of significant discoverers, does not exist in the public consciousness, even his name is known only to those engaged in the history of science.

The comparison between Leeuwenhoek and Joblot raises a number of important ethical questions. Leeuwenhoek made a series of extremely important discoveries, while Joblot mainly described Infusoria and other unicellular organisms, most of which were already known. Leeuwenhoek made his observations with microscopes he created himself, almost always of only one type, while Joblot used a variety of microscopes, simple and compound, created for him by others. Leeuwenhoek's microscopes had a simple and rough mechanical design but with impressive optical capabilities while Joblot used a variety of devices some of which were advanced for their time. Leeuwenhoek kept the polishing methods of his lenses a secret, while Joblot provides in his book detailed instructions on how his microscopes are manufactured.

© Microscope History all rights reserved

© Microscope History all rights reserved

© Microscope History all rights reserved

Musschenbroek- type first form microscope, SML 1695-1705

But most of all, Joblot made observations of the behavior of the organisms he observed, described their movements, and even tried to formulate them graphically. It goes without saying that he did not follow a regulated scientific method, but in this, he was no different from others of his time. (See Ratcliff 2009).

In his book, Joblot (1718) devotes an entire section to describing the microscopes used by him, including single and compound, while providing details on the structure and design and guidelines for their use. The microscope seen here appears as one of the devices from the single group, allowing observations of opaque objects at low magnifications. The microscope is shown in Table 2 Figure 10 (shown here), and in the text, Joblot indicates in two places (left),that the microscopes were "executed" by Monsieur le Fevbre, tres-habile Ingenieur pour la construction des instruments de Mathematique. From this, we can conclude that Mr. le Fevbre was the maker of at least part of Joblot's microscopes. Therefore, the small sticker in the inner part of this microscope's etui, reading: Le Febvre au neuf-Marché refers to this maker.

© Microscope History all rights reserved

It is probable that Joblot was led to his research on microscopy by the arrival in Paris of Christiaan Huygens (1629 – 1695) and Nicolaas Hartsoeker (1656 - 1725) in 1678. In July of that year, Huygens showed microscopes that he had brought from Holland and demonstrated infusoria before the Academy of Sciences. His microscopes were made by the workshop of the van Musschenbroek family in Leiden, after a method of lens polishing that Johan Joosten van Musschenbroek (and also Baruch de Spinoza) learned from the Amsterdam optician and politician Johannes Hudde (Ruestow 1996: 22-28; Bolt et al. 2018). Joblot was probably influenced by Musschenbroek's low-powered microscope (above), which this microscope very likely imitates but with some improvements.

The frontispiece of the second part of Joblot's book presents a line drawing of a naturalist sited in his study room and looking through a single microscope towards the light of the window. Near him and on the floor there are other, compound microscopes. Standing on the table there are also an armillary sphere, a notebook and pen, and several containers. It is believed to show Joblot in his laboratory, inspecting the organisms described in his book.

From Joblot 1718

From Bion 1709

From Joblot 1718

© Microscope History all rights reserved

© Microscope History all rights reserved

Boerhaave V26951

At the same time as Joblot began to make his microscopic observations, this microscope was also advertized by Nicolas Bion (ca. 1652-1733), a maker but most likely also a great retailer of mathematical and astronomical instruments and a royal maker of mathematical instruments for King Louis XIV (1638-1715). His workshop was located in Quai de l'Horloge, Paris. In Bion's profusely illustrated treatise (1709) on the construction and use of mathematical instruments, this microscope is seen (above) together with two other typical microscopes from the end of the 17th to the beginning of the 18th century. Indeed, Joblot's book was published by the same Parisian publisher who published Bion's treatise nine years earlier.

An identical microscope with a similar case but a slightly different circular base is No. V26951 in the Rijksmuseum Boerhaave in Leiden, the Netherlands.

Nicolas Bion (ca. 1652-1733)

Thomin's Later Version of Joblot's Single Microscope, ~1740 (Inv. YG-20-024)

A slightly simpler version of the Joblot microscope appears in small quantities later in the first half of the 18th century and is shown here. This microscope may also have a compatible etui, but it is not preserved with any of the few examples familiar to us today. The original design became simpler and the lens housing and stage made of blackened ivory disappeared. The tweezers remained and on the other side the round stage was replaced with a spike on which a small insect or part of a plant could be impaled. It is possible that an ivory disc was adapted to be mounted on the spike, both as a stab wound and as a stage for observations in small crumbs, similar to the later design of stage tweezers on compound microscopes. But even here, we do not know of any cases in which this part has been preserved.

An accurate description of this microscope appears in Marc Thomin's book from 1749. The illustration does depict this microscope with a disc on the spike as suggested above.

From Thomin 1749

© Microscope History all rights reserved

References

-

Bion, N. 1709. Traité de la Construction et des Principaux Usages des Instruments de Mathematique Avec les Figures necessaires pour l'intelligence de ce Traité. Paris: Veuve Boudot, J. Collombat et J. Boudot fils.

-

Bolt, M., Cocquyt, T. and Korey, M. 2018. Johannes Hudde and His Flameworked Microscope Lenses. Journal of Glass Studies 60: 207-222.

-

Joblot, L. 1718. Descriptions et usages de plusieurs nouveaux microscopes tant simples que composez, avec de nouvelles observations faites sur une multitude innombrable d'insectes et d'autres animaux de diverses espèces qui naissent dans les liqueurs préparées et dans celles qui ne le sont point. Paris: Veuve Boudot, J. Collombat et J. Boudot fils.

-

Ratcliff, M,J, 2009. The Quest for the Invisible: Microscopy in the Enlightenment. London: Routledge.

-

Ruestow, E.G. 1996. The Microscope in the Dutch Republic: The Shaping of Discovery. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

-

Thomin, M. 1749. Traité d'optique mécanique. Paris: Coignard.